The Byrd Center Takes Flight

Part 3: Admiral Richard E. Byrd at the Ohio State University

This is Part 3 of a multi-part series on the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center at the Ohio State University.

In Part 1 and Part 2, we met two founding spirits of the erstwhile Institute of Polar Studies at the Ohio State University: Dr. Richard Goldthwait and Dr. Colin Bull.

None of their Antarctic research would have been possible, however, without the groundwork laid by one of Antarctica’s busiest explorers, Admiral Richard Evelyn Byrd.

Who was Admiral Byrd and why did OSU’s Institute of Polar Studies change its name to honor a man with no connection to Ohio?

To answer those questions we have to look back a century, to the high-flying decade of the 1920s.

The Roaring Twenties meet the Roaring Forties

The dream of Antarctic flight got off to a bumpy start. In 1911, Australian explorer Douglas Mawson brought an airplane to the Antarctic. Well…half an airplane. Mawson’s Vickers R.E.P. Type Monoplane crashed disastrously before the expedition left Australia. To salvage his investment, Mawson cut off the wings and made an “air tractor.” (The air tractor is apparently still in Antarctica, buried under three meters of ice.)

Always looking to make a splash, Ernest Shackleton likewise planned to assemble an Avro “Baby” seaplane for his final expedition in 1921. The crew had to make so many unscheduled stops on their way south that they ran out of time to pick up the parts from Cape Town. Shackleton died in January 1922, before the expedition had even reached the Antarctic continent.

A combination of American cash and Australian derring-do got the first airplane into Antarctic skies. William Randolph Hearst—immortalized as the ruthless media tycoon at the center of Orson Wells’s Citizen Kane—wanted drama for his newspapers. Hearst was known for trying to generate news as well as report on it (and has even been accused of starting a war to boost circulation). He funded Sir George Hubert Wilkins, a dashing Australian war hero, who flew roughly 600 miles over the Antarctic peninsula on December 20, 1928.

Back in the United States, though, a young graduate of the Naval Academy had his eyes on a bigger prize: the South Pole.

Who was Richard Evelyn Byrd?

Richard Evelyn Byrd, Jr. was born into American aristocracy. The Byrds were the sort of Virginia clan that could speak knowingly of the F.F.V.—“First Families of Virginia.” Byrd’s father was friends with Woodrow Wilson, and young Byrd would befriend an equally young Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The Byrds were businessmen and politicians, with a strong sense of Southern honor (and some equally strong prejudices). It is to the credit of the junior Byrd that he would eventually become the first expedition leader in the world to welcome a Black man to the Antarctic. (The man in question, George W. Gibbs, Jr., was extraordinary in his own right.)

Byrd supposedly made the first flight over the North Pole in 1926, but his claim was disputed. The next year he narrowly missed the window to make the first trans-Atlantic flight, suffering a failed test flight that grounded his crew just days before Charles Lindbergh took the prize.

The South Pole was one last geographic “first” for an aviator. In a way, Byrd took a page from his mentor Roald Amundsen’s playbook: Can’t have the North Pole? Go South, young man.

On November 28, 1929, Byrd made the historic flight over the South Pole in a thoroughly documented 18 hours, 41 minutes. He took a co-pilot, a radioman, and a photographer. His exclusive contract with the New York Times—competitor to Hearst’s newspaper empire—ensured glowing coverage. This time, no one would question his achievement.

Byrd’s Legacy Comes to OSU

Byrd would go on to lead four more expeditions to the Antarctic over the following two decades: Byrd Antarctic Expedition II (1933-1934), the U.S. Antarctic Service Expedition (1939-1940), Operation High Jump (1946-1947), and Operation Deepfreeze I (1955-1956) in preparation for the International Geophysical Year.

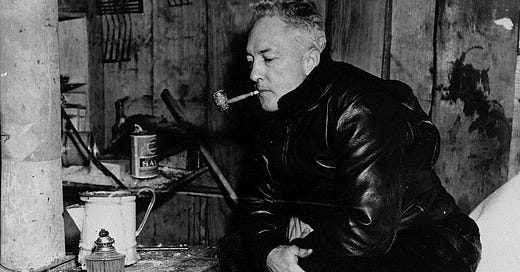

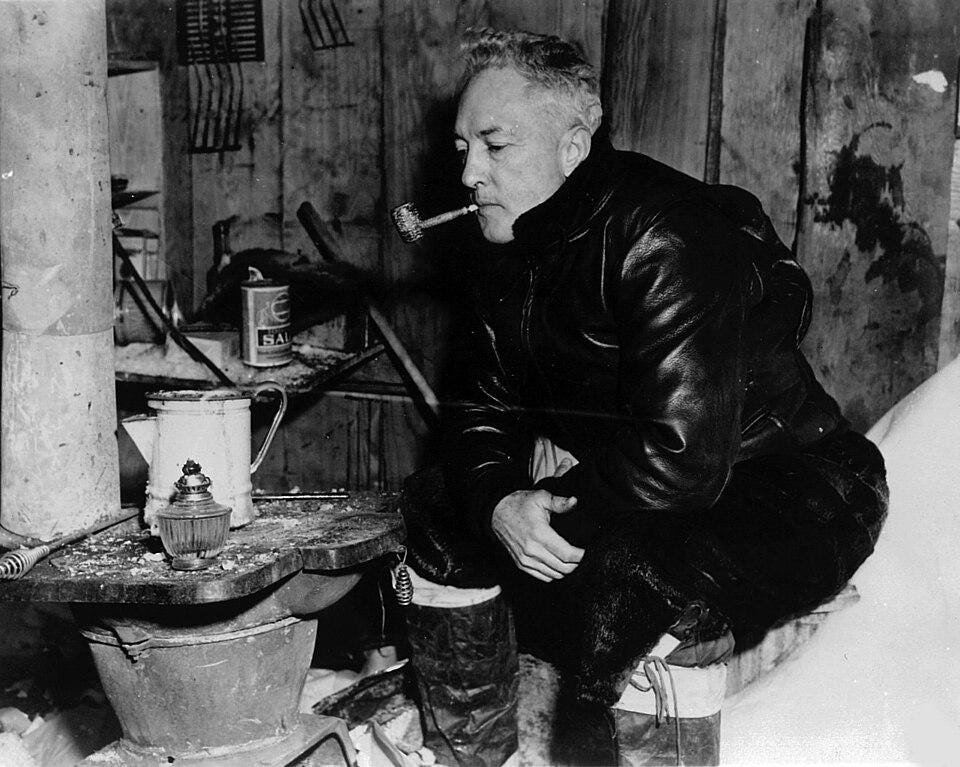

Byrd’s second expedition had been especially grueling. Byrd set up a weather monitoring station deep in the Antarctic interior, at 80°08'S. He ended up manning the station alone through the Antarctic winter of 1934. Ice buildup damaged his ventilation system and when he collapsed from severe carbon monoxide poisoning, Byrd was stranded 123 miles from help. He survived the ordeal—documented in his powerful narrative Alone—but his health never fully recovered. He died of heart failure in 1957 at the age of 68.

Byrd had kept diaries, correspondence with expedition members, medals from Congress, organizational records, newspaper clippings, and even clothing he wore in the Antarctic. This polar treasure was stored in a haphazard way (including in a barn) until being made available for purchase in the mid-1980s. Interested educational institutions had to submit proposals showing their commitment to advancing polar studies.

As part of its proposal to acquire the collection, the Ohio State University highlighted the impressive work of its Institute of Polar Studies—and, to clinch the deal, offered to change the Institute’s name to honor Admiral Byrd. In 1987, the Institute of Polar Studies was re-christened the Byrd Polar Research Center. The acquisition included over 1.5 million items, from diaries and handwritten letters to artifacts like snow goggles and even a rare sun compass.

A few years later, OSU also acquired the papers of Byrd’s rival for the title of Antarctica’s most famous aviator, the Hearst-backed Sir George Hubert Wilkins. Now, a century after Wilkins and Byrd first flew over the frozen continent, their archives are still bringing these ice eagles to life.