The Birth of Cool at OSU

Part 2: Say hello to the The Institute of Polar Studies

This is Part 2 of a multi-part series on the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center at the Ohio State University.

In Part 1, we met an adventurous polar geologist, Richard Goldthwait (aka Doc G) who coordinated the U.S.’s geology and glaciology teams in Antarctica during the International Geophysical Year of 1957-1958.

When Goldthwait got back to the United States he brought huge quantities of data. To learn anything from that raw information, his team at the Ohio State University had to “reduce” it, removing irrelevant or duplicate data points and simplifying the datasets for more efficient analysis. Goldthwait began to assemble funds, infrastructure, brainpower—in short, the makings of a research center.

Goldthwait also brought back a new colleague, Dr. Colin Bull. A transplant from England, Bull had been working as a solid state physicist at Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand, where the two met. Goldthwait had a proposal for Bull: they were already reducing all this data at OSU…why not make it official? Would he help found a polar research institute?

Bull had to make a choice. In 1961 he faced not one—not two—not three—but five job offers from universities around the world. The decision was so daunting that he and his wife spun coins. “It came down to Ohio,” he recalls in a 2000 interview.

The coins may have had help, Bull admits:

“I guess that if the coin had not come down that way, we would have tossed them again, or something. So we looked up Columbus, Ohio, on the map, and it had got "pig belt" right across and it had got "corn belt" right across and it had got "Bible Belt" right across. And we thought to ourselves, "My God, what is this place? Let's go and see." So we went to the Ohio State University on a 15-month appointment and we stayed for 25 years, which shows that some of us are slow learners.”

The initial work wasn’t glamorous. As Bull remarks, “there's not too much that's more boring in the whole of life than two guys sitting in one room reducing data.”

To get data, though, you need to go explore, and that was the fun part. The fledgling Institute of Polar Studies sent researchers across the Arctic and Antarctic, from the Icefield Ranges in the Yukon down to the Nilsen Plateau in the Transantarctic Mountains. According to a 1969 report, the Institute hosted 90 projects in its first seven years, with a cumulative total of $2,121,838 in support. Much of that came from the National Science Foundation.

Bull went on a particularly special adventure. In 1962, he had the opportunity to travel to Sukkertoppen, Greenland with one of his life-long heroes, the German-Jewish glaciologist Fritz Loewe. Back in the 1930s, Loewe had traveled to Greenland with Alfred Wegener, the German geologist who first championed the idea that continents might move around. A colleague had denounced Loewe to the Nazi regime upon his return, and briefly imprisoned before he fled to England. A book about that expedition—Eismitte—had inspired 10-year-old Bull to become a glaciologist. Together, Bull and Loewe measured the thickness of the ice in at Sukkertoppen, with the aim of establishing a long-term monitoring station in that part of Greenland.

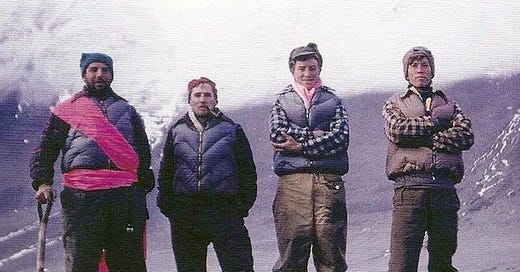

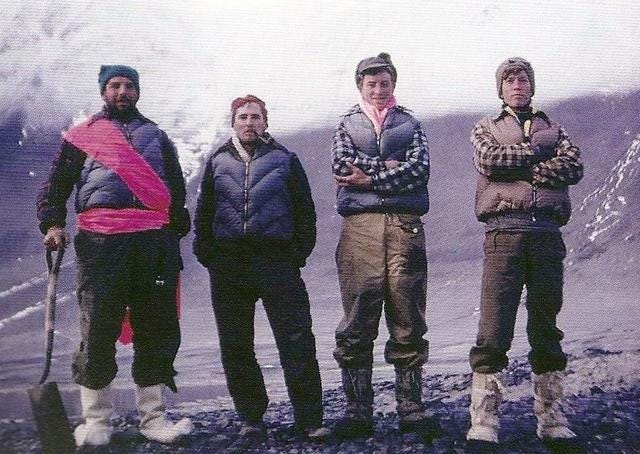

Perhaps Bull’s widest-reaching accomplishment, though—and one of the proudest moments of the early Institute—was advocating for the U.S. Antarctic Program’s first female research team to work on the ice. The Soviet Union had sent their first female scientist to the Antarctic in 1956, but when Bull had tried to send a female researcher south in 1959, the U.S. Navy refused logistical support. Bull—perhaps living up to his surname—pushed back, and a decade later won approval for Lois Jones to lead a four-woman research team to the McMurdo Dry Valleys. On Jones’s OSU-based team were Eileen McSaveney, Kay Lindsay, and Terry Lee Tickhill. They worked in Wright Valley, which (perhaps not coincidentally), had been named by Bull in 1958. Along with Jones’s team came several other female researchers who worked throughout McMurdo Sound, including Christine Müller-Schwarze, Pamela Young, and Jean Pearson. Together, a group of them became the first women to set foot at the South Pole.

Read on for Part 3: The Byrd Center Takes Flight.