Celebrating an Antarctic Hero: George W. Gibbs, Jr.

The first Black person to set foot on the Antarctic continent

An audio version of this post is available on Substack and Spotify.

Last year, I had the honor to hear Leilani Raashida Henry speak about her father, George W. Gibbs, Jr.

Gibbs served in the US Navy aboard the USS Bear, and on January 14, 1940 he made history as the first Black person to set foot on the Antarctic continent.

As Henry shares in her engaging book, The Call of Antarctica (2022), one of her father’s lifelong heroes was the African American Arctic explorer Matthew Henson. Henson became the first person to stand on top of the world—literally—when he arrived at the North Pole almost an hour ahead of Robert Peary and their Inuit companions on April 6, 1909. Gibbs, too, was keen to serve his country while embarking on his own polar adventure.

Not only would Gibbs become part of Antarctic history, but the Antarctic would also become part of his history, shaping the person he became. Gibbs was in his early 30s when he applied to join Admiral Richard Byrd’s United States Antarctic Service Expedition (USASE) of 1939–1941. His experiences during the expedition showed him a very different world from that of the Jim Crow South in which he’d grown up.

The USASE was Admiral Byrd’s third Antarctic expedition and was a classified mission at the time. President FDR had asked the Navy to keep an eye on German activities in the Antarctic, where Hitler had launched his own secret expedition from 1938–1939. As Henry told us during her talk: “There were lots of entries in other diaries, where they were guessing why they were doing this. So the men on the ship really didn’t know why they were going down.”

The USASE was also the first Antarctic expedition to include members of African descent. Gibbs began as a mess attendant, and was joined by two other African American servicemembers aboard the Bear. The challenges of the Antarctic environment meant that hierarchies were flexible. As Henry writes, Gibbs recognized that his mess attendant rank “wouldn’t prevent him from full participation in other assignments on the expedition. In Antarctica with Byrd, rank and race were less important than they were in the United States or on other expeditions.” In addition to his duties preparing and serving food, cleaning laundry, and keeping the ship clean, Gibbs took examinations to get promoted. He eventually became a chief petty officer.

Gibbs found that both the Bear’s Commanding Officer Richard Cruzen (later a decorated Vice Admiral), and Admiral Byrd himself, treated Gibbs with respect and gratitude for his contributions. As Henry tells us, Cruzen reprimanded an officer who insulted Gibbs, and gave Gibbs an official commendation for meritorious service, citing his “zeal, initiative, and untiring industry.” Gibbs’s energy and hard work earned him two such commendations during the expedition. And on a stopover in Valparaiso, Chile, Gibbs recorded in his diary: “Went sight-seeing and had dinner at the Hotel Higgins where the Admiral [Byrd] is staying. In the U.S. it would have been impossible for me to be as welcomed.”

The USS Bear arrived at the US Antarctic base Little America on January 14, 1940. As usual, Gibbs was ready to land a helping hand. He recalled in his diary: “When the Bear came up to the ice close enough for me to get ashore, I was the first man aboard the ship to set foot in Little America and help tie her lines deep into the snow. I met Admiral Byrd; he shook my hand and welcomed me to Little America.”

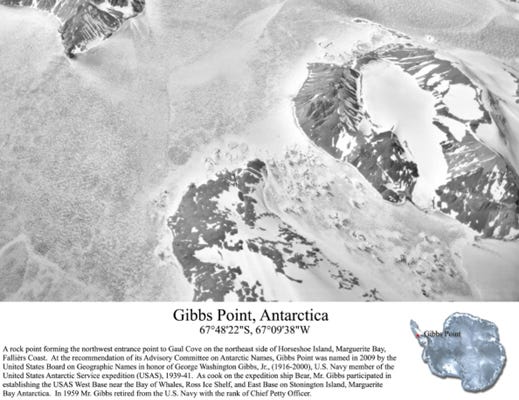

Gibbs wanted to bring that kind of fair and open society back home. When he returned to the US, he set to work. He became a member of the YMCA, Toastmasters, the American Red Cross, and the United Methodist Church. He co-founded the Rochester, MN branch of the NAACP, and became the first African American to be granted membership to the local Elks Club after his initial exclusion raised an outcry. George W. Gibbs, Jr. Elementary School, Minnesota’s first Gold LEED green-building certified school, is named in his honor. His daughter describes Gibbs as upbeat and kind: someone who “treated strangers like his best friend.” Just two days before he passed away in 2000, he volunteered to make phone calls encouraging his fellow citizens to vote. His legacy lives on in Gibbs Point along the Antarctic Peninsula.

A story worth recounting - thank you.