Roll to the South Pole

A boardgame in which Roald Amundsen doesn't always win

An audio version of this post is available on Substack and Spotify.

I recently played my first Antarctic-themed boardgame: Roll to the South Pole. The English version of this game was released by Rio Grande Games in 2012 and is now out of print, but not hard to find online.

Players can choose to be one of several polar explorers—Roald Amundsen (Norway), Robert Scott (Britain), Ernest Shackleton (Britain), Jean-Baptiste Charcot (France), or Wilhelm Filchner (Germany). Historically, only the first three were interested in reaching the South Pole, but all five of them led roughly contemporaneous expeditions to the Antarctic in the early 20th century.

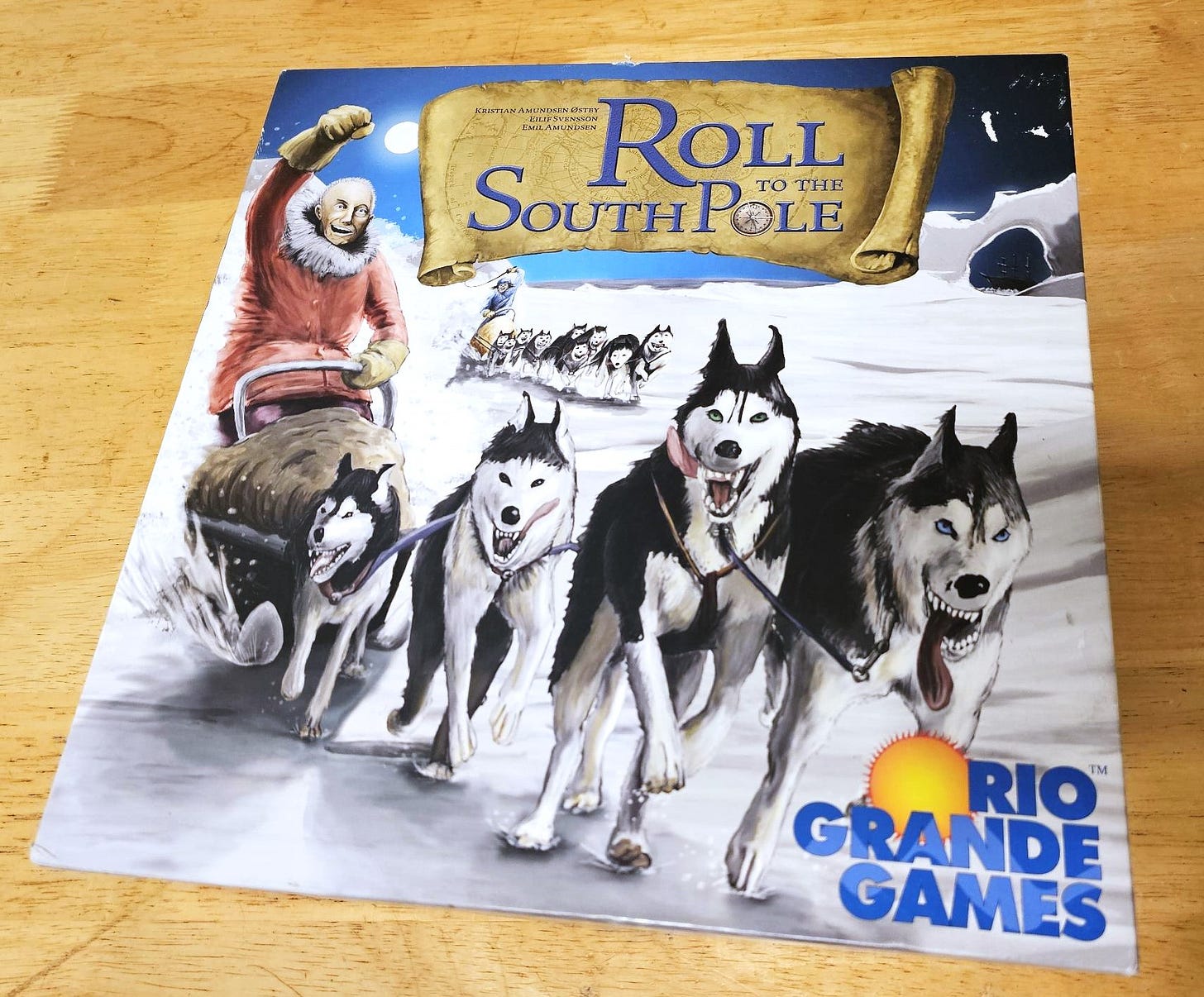

Judging by their names—Emil Amundsen, Kristian Amundsen Østby, and Eilif Svensson—the game’s designers have an explorer in this race. While I wasn’t able to determine their exact connection (if any) to the great polar explorer, the cover image of a wickedly grinning Roald Amundsen pumping his fist in the air speaks volumes. Captain Scott can be seen behind him, mushing a formidable team of sled dogs, as though to say: if only. (Scott, who arrived at the Pole five weeks behind Amundsen in 1912, didn’t use sled dogs.) Even more pointed is a remark in the game’s instructions: “The first player to place all his/her flag markers has reached the South Pole, and wins the game. The game ends immediately. As in real life, no one cares about the second place.”

Did Team Amundsen have to rub it in?

(Incidentally, Charcot won the first game we played; Shackleton—my character—put up a stiff fight but accepted defeat with characteristic grace.)

As the game’s title suggests, one plays by rolling six dice. The dice are color-coded to match different kinds of terrain on the board: black for rocks, blue for ice, white for snow. If you roll a large enough number on the correct dice to move across the terrain, you get closer to the “flag” spaces, where you can begin planting flags. You must plant four flags successfully to win. (Full instructions can be found here.)

As far as I can tell, no kind of terrain is easier or harder to pass successfully than any other. The terrain instead functions as a decision point: the game includes five dice of each color for a total of 15, and players choose which six dice to select, based on what kind of terrain they expect to encounter on their turn. Most terrain spaces are occupied by color-coded terrain cards placed face-down. These terrain cards often carry a surprise when one turns them over: an icy blue card may also require a roll for white, which becomes more difficult (though not impossible) if one did not choose any white dice. There are workarounds for such dilemmas by spending “strength cubes.” Luck, strategy, and access to resources all come into play.

It is difficult for a game to capture the challenges and decision-points of Heroic Age Antarctic exploration, and this game doesn’t try. However, it hews to historical reality in a few ways. Pre-printed tents on some spaces suggest depots already laid down in preparatory journeys (although these don’t actually give you anything), while historical anecdotes in the instructions bring some context to the gameplay.

Most significant, though, is that combination of luck, strategy, and resources I mentioned. Roald Amundsen famously remarked that “Victory awaits him who has everything in order — luck, people call it. Defeat is certain for him who has neglected to take the necessary precautions in time; this is called bad luck.”

Despite Amundsen’s remarks, variants of the words “luck” and “fortune” appear repeatedly in the English translation of his 1912 account, The South Pole. One would be hard pressed to assume these are all just sour grape insertions by the British translator. Amundsen understood that, in the hostile Antarctic, humans are never in control. The best they can do is to create a buffer of strategy and resources that will hopefully prevent bad luck from becoming fatal. In recent years, Captain Scott has been blamed for poor planning, but his questionable decisions alone did not kill his men. Rather, those decisions made the team more vulnerable to bad luck. By the end, they were walking a knife’s edge.

For the record, playing as Amundsen doesn’t confer any special benefit—unless you count the psychological boost of seeing your name and face all over the game’s cover and instructions. Don’t underestimate the power of morale!

If you decide to roll your way to the South Pole, I wish you a well-chosen route, many strength cubes, and a little bit of luck.