Day 8 @ Byrd Polar Archives: Encounters with the Doomsday Glacier

"Davy Jones' deep freeze locker"

My archival quest today turned up two bits of sunken treasure:

The answer to a question that had been bugging me (and some longtime Antarcticans) about the Doomsday Glacier.

An insight into the power of unscripted exploration.

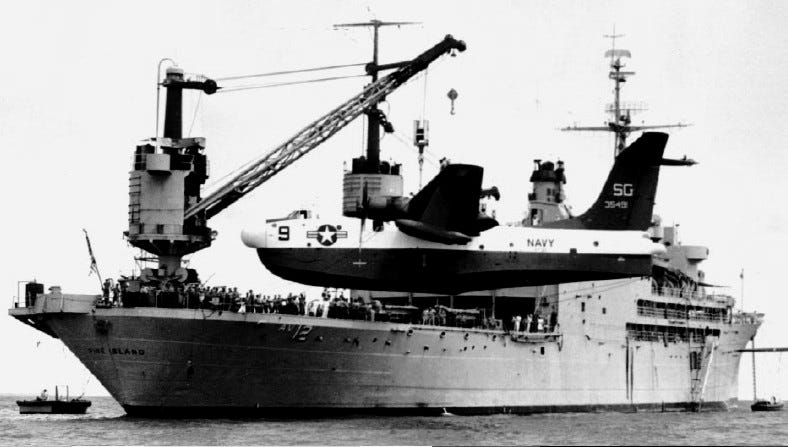

Neither of my nuggets—pieces of eight—arrowheads—choose your loot!—came from any bigwig. They were both in the diary of a wide-eyed young man from Ohio, Richard “Dick” Lockhart, who shipped aboard the U.S.S. Pine Island as a Naval Ensign in 1946.

An Antarctic Detective Story: Arrival at Pine Island Bay

A few years ago, I wrote a piece on Thwaites, the so-called “Doomsday Glacier.” It’s the glacier of doom because (a) it’s a keystone within the West Antarctic Ice Sheet and because (b) it’s unstable. Thwaites is huge and hugely important; if it collapses—as most glaciologists now believe it certainly will—the West Antarctic Ice Sheet will follow.

A question bothered me, though.

Glacial geologist Terry Hughes (incidentally, a former OSU researcher) had started worrying about Thwaites and its neighboring Pine Island Glacier in the late 1970s. Why did it take 40 years for the global community to come together and focus resources on this threat?

I talked to around a dozen scientists who had worked in Antarctica for decades and pieced together an answer that made sense to me. Part of the story had to do with weather: the Amundsen Sea region around Pine Island Bay is notoriously icy and stormy. (If you’d like the whole story, feel free to check out the article at Hakai).

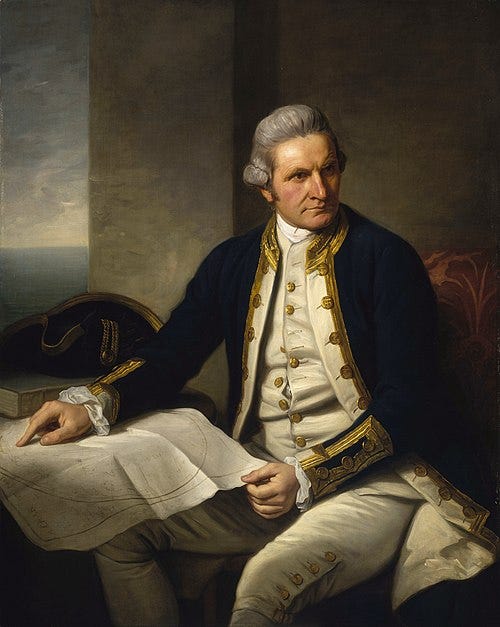

In fact, the Amundsen Sea is so hostile that it held another, less well-known distinction: For over 200 years, no one sailed further south in those waters than Captain James Cook.

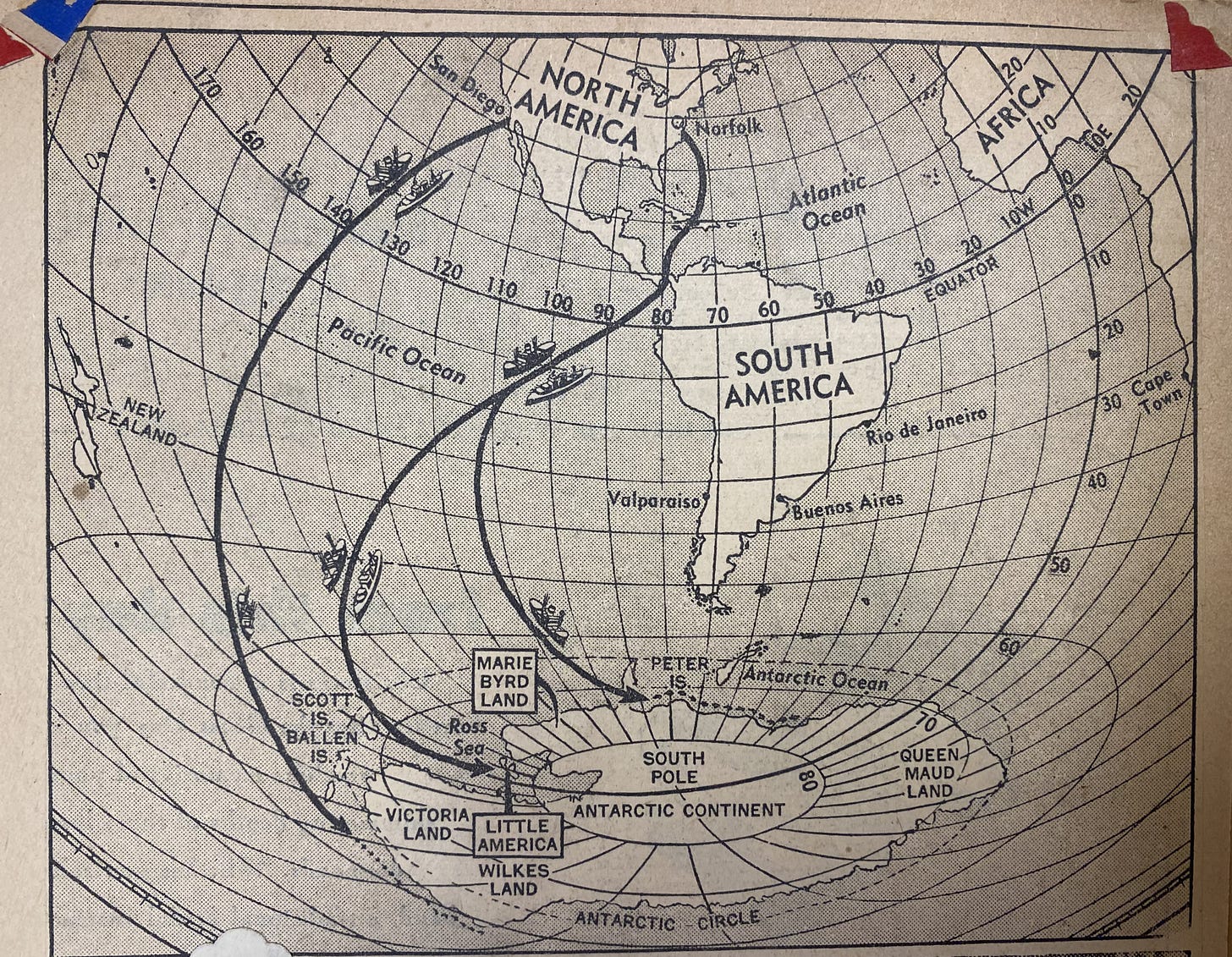

Not only did Captain Cook hold the record, but that region is where he set his record. On January 30, 1774, Cook’s crew reached the southernmost point ever recorded, 71°10′ South. That latitude became famous, a challenge to generations of explorers. (I’ve written about that voyage here.) What’s less often remembered was Cook’s longitude: 106°54′ West.

He was around 100 miles directly north of Thwaites Glacier. When an edition of his journals appeared in 1971, a footnote pointed out that his record still held in that region. No one had sailed further south in the Amundsen Sea than Cook.

Which raised another question. This time, no one could answer.

What about the U.S.S. Pine Island?

Pine Island Glacier is next door to Thwaites, and both glaciers feed into Pine Island Bay. The glacier and bay were named for the ship, which itself had been named for Pine Island Sound in Florida.

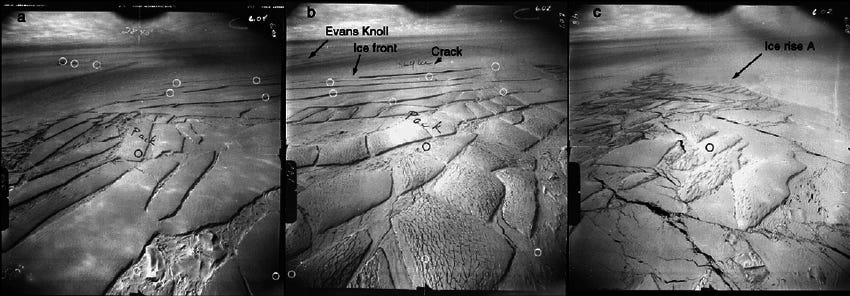

Planes launched from the U.S.S. Pine Island had discovered the bay in 1947. Had it not sailed there?

Presumably the ship’s log had the answer. That would be held either at the National Archives or in the records attached to the ship’s home port. I never did manage to chase it down.

So when I got to OSU, I was intrigued by the collection of one Richard Lockhart. He’d been aboard the Pine Island in 1946-1947 and he’d kept a diary. What’s more, the diary has daily entries…and they’re legible.

I knew from aerial photographs that a reconnaissance flight had gone out in January of 1947. But when you read someone’s personal diary, it feels strange—even disrespectful—to cut straight to the goal. I wanted to know what kind of person Dick Lockhart was. So I started from the beginning.

In December of 1946, young Ensign Lockhart had a lot on his mind. On December 12, he crossed the Equator for the first time and was inducted into the order of Shellbacks by King Neptune—a ceremony that probably hasn’t changed much since Cook’s day, except that the certificates might be fancier.

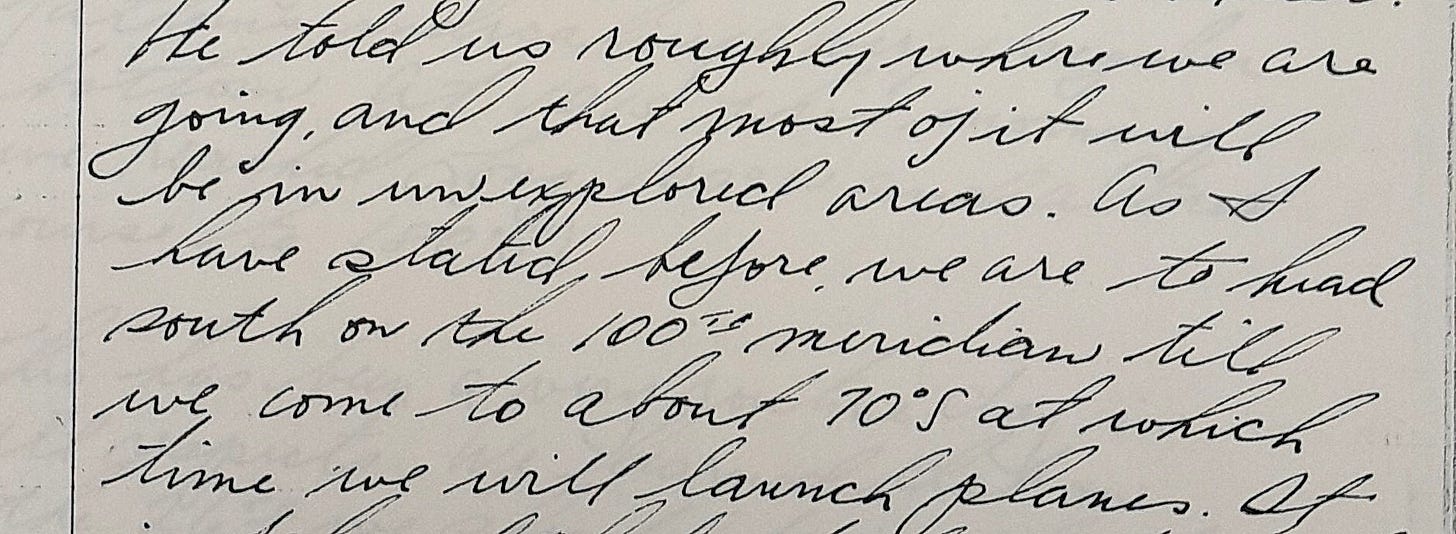

By December 18th the crew had been briefed on their destination: they would sail south along the 100th meridian until they reached 70° South, and then would launch planes. That’s roughly one degree of latitude—a little over 70 miles—short of Cook’s southernmost point. But if anyone onboard knew that Cook still held the record around there, Lockart doesn’t mention it.

Then, just after Christmas, disaster struck. A seaplane accompanying the Pine Island set off on a routine flight and never returned. Fog and foul weather prevented rescue flights for two weeks. Finally, on January 12, six survivors were found and brought back to the ship. Among the dead was Ensign Maxwell Lopez, whom Lockhart describes in a letter as a “good buddy of mine, who now lies buried in the snow on Cape Hart.”

The bad weather didn’t stop. There was a reason this remained an “unexplored area.” The fog persisted, and at one point the Pine Island collided with ice so violently that Lockhart thought their companion ship had hit them. On January 19, they had yet another crash: one of the “whirligigs” missed the ship and made a hard landing in the ocean, with the ship’s commander George Dufek aboard. No one was killed, but Lockhart reports: “Scratch one helicopter.”

There was so much ice that for days the ship would barely move. Lockhart describes the pack ice as a “mousetrap” and refers to the region as “Davy Jones’ deep freeze locker.”

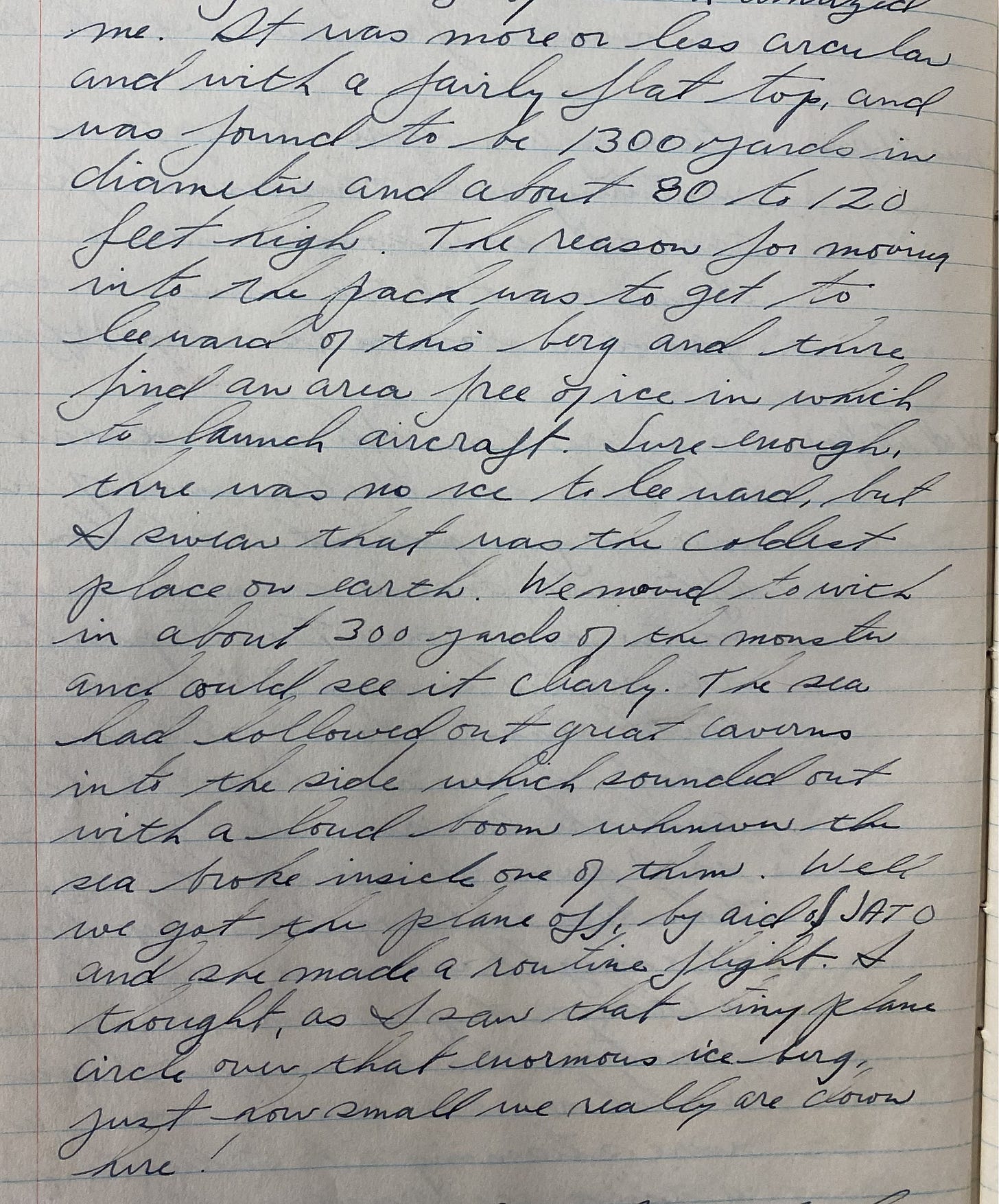

On January 23rd, they came into the company of a monster iceberg. Its diameter was 10 times the length of a modern football field, and it loomed 100 feet above the water. A berg that big should be fairly stable, and offers protection from the wind. “Sure enough,” Lockhart writes, “there was no ice to leeward.” They pulled into the lee of the berg and launched a seaplane from the water.

“I thought, as I saw that tiny plane circle over that enormous iceberg, just how small we really are down here!” Lockhart writes.

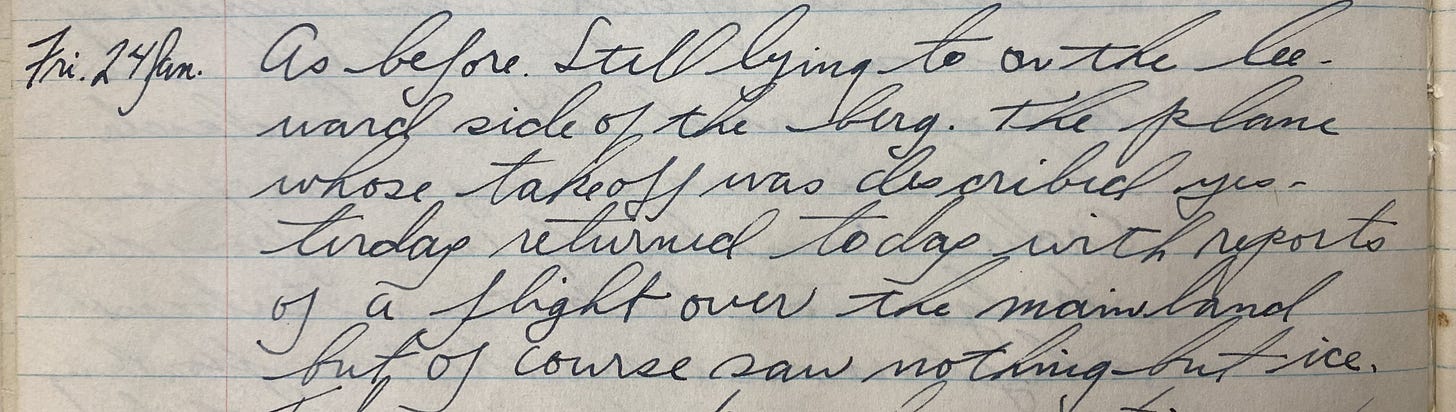

They settled down to wait. “I swear that was the coldest place on earth,” Lockhart remarks. The next day, the plane returned and reported that it had made a flight over the mainland. “But of course saw nothing but ice,” Lockhart notes.

And that was it. They never sailed to Pine Island Bay; they may have beaten Cook’s record, but if so, no one paid much attention. They were off to the Peninsula next, to finish their cruise.

The Beauty of Basic Science

“Nothing but ice.”

Lockhart couldn’t possibly know how important that ice would be to his children and grandchildren’s generations. He couldn’t know, in 1947, how many people would spend untold hours examining those photographs of “nothing but ice” for clues into its past and future. He couldn’t know that a cavity had just begun to open beneath Pine Island Glacier, devouring its “weak underbelly” from within. He couldn’t know that the ice named for his ship—indeed, all the ice in “Davy Jones’ deep freeze locker”—would threaten to transform our planet.

To me, that’s amazing. Lockhart was willing to endure sleepless nights, early watches, biting cold, the rolling and pitching of the ship, all in the name of discovery. His friend Ensign Lopez lost his life in the service of that same goal. On other expeditions, men would complain that they were serving only their commanders’ egos. They wanted meaning: to be part of something greater than themselves and the petty ambitions of Commodores and Admirals. They wanted to expand the boundaries of human knowledge and capability.

Ensign Lockhart didn’t know how important those photographs were, just as he didn’t know that he was on the cusp of breaking a 200-year-old record. We never know what our exploring, questioning, questing minds might turn up.

Should that stop us?